With the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) poised to put a highly-anticipated vote into action on February 8, and electioneering in full swing, observers, local as well as international, are wondering how many voters will this hoopla draw out on the democracy’s biggest decision-making day.

Put pragmatically, this isn’t just another cutthroat race for power; it’s in the truest sense a referendum on the future of 241.5 million people of Pakistan.

A crippled economy, record-high inflation, joblessness, smouldering social struggles, security threats, and the ever-hanging sword of the ‘powers that be’ demand the voters to come out and have their say.

But will they?

Let’s dive into the factors shaping voter turnout in Pakistan’s 2024 election, breaking down the hopes, fears, and motivations having the potential to swing participation and the eventual outcome of polls.

According to available statistics, the highest voter turnout in Paksitan’s history was 63% (1970), while the lowest was recorded at 35% (1997), which raises many questions because of this huge fluctuation. Here’s an election-by-election analysis of the voter turnout since 1970.

Elections 1970

Being the first-ever direct general elections in the country, the 1970 elections witnessed the highest turnout, a total of 25,730,280 voters were registered and 16,318,808 of them exercised their right to vote.

Punjab led with a 69% turnout, while Balochistan had the lowest at 41%. Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa recorded turnouts of 60% and 48%, respectively.

Former Herald Magazine editor and Lok Sujag co-founder, Badar Alam, attributed the high participation to public enthusiasm, given that, previously, only a specific group could vote.

Additionally, he highlighted the transparency of these elections, marking the most transparent in the country’s history, where no party’s victory was predetermined. Consequently, each political party worked diligently to mobilise its supporters.

1977: A fall in turnout

The general election of 1977 saw a turnout of 54% with 29,883,212 registered voters, marking a 9% reduction from the previous elections. Turnout remained relatively higher in Punjab at 64% and KP (erstwhile NWFP) at 42%, but it fell drastically in Sindh to 32% and Balochistan to only 27%. Various factors, such as political instability, insufficient faith in the electoral system, and notably the East Pakistan Liberation War in 1971, contributed to the lower turnout.

1985: Controversy and boycotts

The 1985 elections were controversial, with many opposition parties boycotting the elections. Benazir Bhutto, the leader of the largest political party — the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), was exiled after Bhutto’s hanging. The non-party-based elections also contributed to the low turnout, with 52.93% of 32,589,996 voters participating.

1988 elections: Return to democracy and challenges

Although the 1988 general elections signalled the country’s return to democracy, the turnout fell further to 43.07%. Punjab again recorded the highest turnout at 45%, while Balochistan had the lowest at 26%. The ID card rule for voters negatively impacted the turnout, and the election was marred by allegations of rigging. The PPP formed a coalition government, but it couldn’t last even two years, as Benazir’s government was overthrown by Ghulam Ishaq Khan with the support of then-army chief General Aslam Mirza Baig.

1990: Surge amid challenges

In the 1990 general elections, there was a minor surge, and the overall turnout was 45.46% with 46,607,233 total registered voters. Punjab led in turnout with 50%, followed by Sindh at 43%, KP at 36%, while Balochistan at 29% remained the lowest.

On election day, reports of violent and intimidating acts, such as kidnappings, shootings, disturbances at polling stations, and harassment of voters, emerged. These incidents may have led to people being unable to vote in affected areas. Furthermore, before the election day, authorities arrested supporters of the Pakistan Democratic Alliance (PDA) in certain constituencies in Sindh and other parts of the country as a means of intimidation.

1993: Another decline

The 1993 elections witnessed another downward trend in turnout, remaining at 40.28%. The Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) boycotted the National Assembly’s elections but contested provincial seats. Punjab’s turnout was reduced to 47% in 1993, while Sindh saw a major drop to 28%, and KP and Balochistan stood at 26%.

1997: Record-low turnout

Farooq Laghari removed then-Prime Minister Benazir from office on November 5, 1996, citing accusations of corruption and abuse of power by her administration. The year 1997 saw a record-low voter turnout of only 35%, which remains the lowest in Pakistan’s electoral history.

2002: Constitutional changes impact turnout

The 2002 general elections took place in the context of a constitutional referendum held in April 2002, which resulted in the prohibition of leaders of two major political parties, former Prime Ministers Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto, and numerous others from participating in the elections.

As a result of the constitutional referendum, General Pervez Musharraf was granted an additional five years in power and gained significant influence over the newly formed government. Although the PPP-P received the highest number of votes in the National Assembly elections of 2002, it was the PML-Q that secured the most seats.

Voter turnout remained at 41.80%, with Punjab once again topping at 46.32%, Sindh seeing 36.79% turnout while KP and Balochistan stood at 33.22% and 27.2%, respectively. Alam believes that in the 2002 elections, there was no political mobilisation or enthusiasm in the campaign.

Additionally, everyone was aware of the military government’s control, and any elected government would be subordinate to it, resulting in a lack of interest from the public.

Furthermore, Musharraf set a requirement that only individuals who held a bachelor’s degree would be eligible to run for election. As a result, many established politicians with a strong following were unable to participate in the elections.

2008: Terrorism and Benazir’s assassination

Pre-election terrorism and the assassination of Benazir shook the 2008 general elections. The overall turnout was 44.55% with 80,724,153 registered voters. In Punjab, turnout was 48%, Sindh 45%, KPK 33%, and Balochistan 30%.

2013: Increased turnout with PTI’s emergence

In the 2013 general elections, the overall turnout jumped to 53.62% with 83,756,567 registered voters. Punjab again was top of the list with 57%, Sindh 53%, KP 42%, and Balochistan lowest with 36%. Compared to elections held in the country since 1985, the 2013 general elections had a considerably higher voter turnout. This can be attributed to the emergence of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) as the third-largest political party in the country.

2018: Mixed turnout and disqualifications

In the 2018 general elections, only 50.14% of voters took to the elections, with the highest turnout observed in Punjab at 56.8%, while the lowest was in KP at 41.5%. In 2018, Balochistan, with a 45% turnout for the first time, was not the province with the lowest turnout. Both the 2013 and 2018 elections followed the disqualification of two sitting prime ministers, Yousaf Raza Gillani and Nawaz Sharif, further damaging people’s faith in democracy.

Number, and location of polling stations factor in low turnout

Bilal Ijaz Gilani, the executive director of Gallup Pakistan, and Badar Alam both believe that the number and location of polling stations are crucial factors in low turnout, as voters may face difficulty reaching them if they are situated far away.

This has been a recurring issue since 1988, with surveys indicating that people face difficulties reaching the polling stations, particularly women who have to travel 6-7 kilometres in some areas.

Therefore, the need to increase the number of polling stations is emphasised, as the current count of 150,000 is deemed insufficient.

Talking about other factors, Gilani highlighted: “People believe the election process is ineffective and inconsequential. Regardless of the political party in power, they do not prioritise the welfare of the populace and merely feign concern. Consequently, people are disillusioned with this system and lack enthusiasm towards it.”

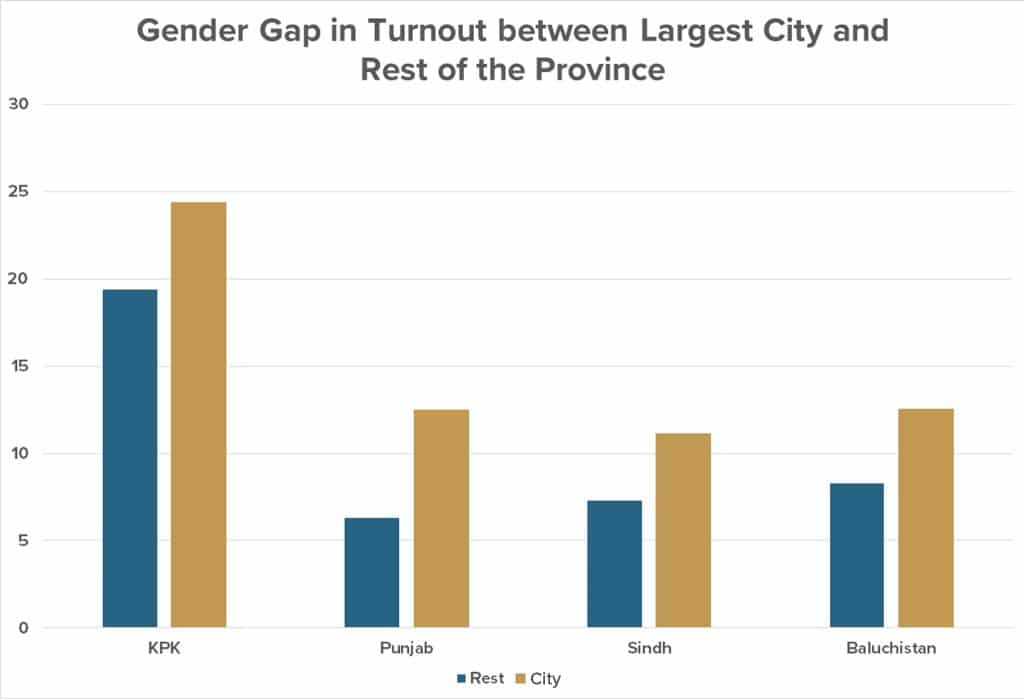

He added that rural areas tend to have a higher voter turnout compared to urban areas, despite common belief that the opposite is true. This can be observed in the city of Karachi, where historically, voter turnout has been low due to a lack of responsibility felt by the citizens.

Many individuals do not want to use their vacation days to vote. The calculation of voter turnout is determined by the voter list. In KP, it is up to the locals to decide whether women should have the right to vote. A major reason why for every 100 men, only 90 women come out to vote.

Alam further added: “Various other factors influence voter turnout in each election. These factors may include scheduling, as extreme weather conditions such as hot summers or severe winters can discourage people from leaving their homes to vote.

Similarly, monsoons and floods can leave people stranded and unable to cast their vote. Finally, the timing of voting is another important consideration. The level of competition in the election is also a significant factor. If a candidate is predicted to have a 75% chance of winning in a particular constituency, the supporters of those who are unlikely to win may not come out to vote for their candidate.”

‘Lack of trust in electoral system’

Ahmad Bilal Mehboob, the founder and director of the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT), has attributed the low voter turnout in our country to the lack of trust in the electoral system.

He explained that this was also the reason for low turnout in the nineties, as even those who were elected could not hold their positions for long.

Mehboob believes that the continuous delay in holding elections and incidents of terrorism have further eroded people’s trust in the system, leading to a decrease in public interest. He warned that if similar incidents occur in Sindh and Punjab, the voter turnout will further decline.

Disparity in turnout between Punjab and Balochistan

Alam said that the voter turnout in Punjab was higher compared to other provinces due to a larger population and easily accessible polling stations. However, he said, recent elections had shown that the voter turnout in Sindh and KP was not significantly lower than in Punjab.

“On the other hand, in Balochistan, there is a selection, not an election, which does not generate much interest from the people.”

Meanwhile, Mehboob thinks that the historical trend of higher voter turnout in Punjab can be attributed to the greater level of “participation and contribution” among the people compared to Balochistan.

The residents of Balochistan perceive a lack of government concern towards their needs. Additionally, certain regions in Balochistan are affected by terrorism, which further contributes to the lower voter turnout in that province.

Abundance of polling stations cause of Punjab’s high turnout

Gilani added that the high voter turnout in Punjab is the abundance of polling stations and the keen interest of both the government and the people in elections. Punjab also has the highest number of seats, which allows the leading party to form the government at the national level. Whereas people in Balochistan, often have to travel long distances to reach polling stations,

Will the loss of its iconic symbol impact PTI’s voter turnout?

Mehboob believes that “The loss of PTI’s symbol could potentially lead to a decrease in voter turnout, the extent of which will depend on the efforts of PTI supporters in informing voters about the party-backed candidates in each constituency.

The impact may not be significant but it is realistic to expect a slight decrease in turnout as some voters may feel discouraged by the perception that the party is unlikely to come to power.

Gilani also believes that voter turnout in upcoming elections will be less than 2018 and 2013 polls. Surveys before 2013 and 2018 GE when compared with surveys now show 10 to 20% less inclination to vote.

This could be based on difficulties that PTI currently faces due to not being able to give tickets to credible political candidates but also that ticket holders stand on different party symbols. Both factors dent people’s inclination to vote but also their ability to convert the intention to vote into the reality of voting.

Badar Alam thinks the primary factor that will significantly influence the election turnout is Imran Khan’s conviction in three cases, making it more crucial than the removal of the party symbol.

This scenario occurred with two political parties, first in 1997 with the PPP and then in 2002 with the PML-N. In 1997, Benazir faced numerous legal cases similar to Imran Khan, which led to a decrease in voter turnout. Similarly, in 2002, PML-N supporters did not appear to cast their votes.

The symbol factor will only come into play if two PTI candidates from the same constituency both claim to be PTI-backed candidates, potentially impacting the electorate.

However, the greater impact lies in Imran Khan’s conviction, as it means he will not have the opportunity to participate in any way after the election. With his absence from Pakistani politics for some time, there will likely be a negative effect on voter turnout, as his supporters may feel disheartened by his lack of participation in the election.

However, Alam believes it can also have a positive impact as PTI candidates are effectively mobilising people in their constituencies, if they are successful, it could have a positive effect on voter turnout because people will cast their “Revenge Vote”, showing that even though their leader was in jail, they would still vote and defeat their opponents.