PNN – As Washington and Moscow move closer to a peace agreement, Europe is using financial and political pressure to prevent a repeat of a “new Yalta” scenario, but will it succeed?

As efforts by Washington and Moscow approach a sensitive phase aimed at ending the war in Ukraine, Europe’s obstruction of the peace track has intensified, revealing a deep rift over the future of the negotiations. This divide goes beyond confrontational narratives and is rooted in serious concern among European capitals about being excluded from the decision-making process. Europe, which has borne heavy political and economic costs from the war in recent years, now fears that a hasty agreement between major powers, without regard for the continent’s security considerations, could reduce its role to that of a “payer with no effective share in the final decision.”

Dmitry Polyanskiy, Russia’s deputy permanent representative to the United Nations, said a few days ago during a UN Security Council meeting, stressing that “Ukraine’s European allies are preventing peace talks from reaching a result,” that the European partners of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky are “actively seeking to undermine the peace initiatives proposed by Russia and the United States.”

According to observers, European capitals in recent months have been gripped by deep anxiety rooted in 80 years of post–World War II history: fear of a repeat of the 1945 Yalta Conference, when the leaders of the United States, the Soviet Union and Britain decided the map of influence in Europe without the presence of other European countries. Now that Donald Trump has returned to the White House and, with a deal-oriented approach, is seeking a rapid agreement with Vladimir Putin, Europe sees itself once again at risk of being excluded from decisions about its own fate—a continent that has spent more than 170 billion euros to support Ukraine, yet may ultimately be left as a payer without voting rights.

Europe’s struggle to assert its presence and transform from an anxious spectator into a main player

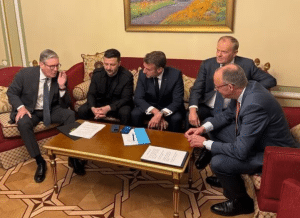

Despite Trump formally sidelining Europe from the Ukraine peace talks, the December 8, 2025 meeting in London marked a turning point in Europe’s efforts to step out of the margins of history. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Friedrich Merz met with Volodymyr Zelensky in an extraordinary session to send a clear message to Washington and Moscow: Europe is neither on the sidelines of the negotiations nor a passive observer.

The meeting was part of recent months’ efforts to craft a “European version of peace,” a framework built on four pillars: firm security guarantees for Ukraine, linking the peace horizon to Kyiv’s path toward EU membership, using frozen Russian assets for reconstruction, and maintaining part of the sanctions as leverage.

However, many experts as well as Russian officials interpret these moves as “obstruction” to the peace process. From Moscow’s perspective, Europeans, by imposing strict conditions and insisting on extensive security guarantees, are in effect seeking to block an agreement between Washington and the Kremlin.

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council, reacted to proposals to deploy European forces to Ukraine as peace guarantors by stating bluntly that “NATO forces cannot serve as peacekeepers, and Russia will not accept such a security guarantee.” This hardline stance underscores that Europe’s attempt to play a central role in the postwar security architecture faces serious resistance from Moscow.

At the same time, the disclosure of Trump’s 28-point peace plan in November 2025 sent shockwaves through European capitals. Drafted with the direct involvement of Kirill Dmitriev, Russia’s special envoy, the plan included formal US recognition of Russian-occupied territories, limiting Ukraine’s army to 800,000 troops, and joint US-Russian decision-making over the fate of frozen assets. For Europeans, the plan was not a peace proposal but “Ukraine’s surrender” to Moscow. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stressed in a speech to the European Parliament that “any peace agreement must guarantee European security, not leave the door open to the disintegration of countries or the redrawing of borders by force.”

Europe’s effort to move from an anxious bystander to a key player also faces serious internal obstacles. Eastern European countries maintain a tougher stance against any concessions to Russia, while segments of public opinion in Western and Southern Europe are weary of the protracted war and its economic consequences. These divisions have led many observers to view talk of a European peace plan as more rhetorical than a coherent proposal backed by genuine consensus.

Europe’s leverage tactics: from asset freezes to multilayered sanctions

In recent days, the European Union has turned to its most powerful financial lever against Russia: frozen assets. On December 12, 2025, EU governments in the European Council invoked Article 122 of the EU treaties—which requires only a qualified majority vote and bypasses the European Parliament—to decide on the indefinite freezing of 210 billion euros (246 billion dollars) in Russian central bank assets.

This indefinite freeze forms the main groundwork for the EU’s proposed compensatory loan to Ukraine. Under the plan, the bloc intends to use 185 billion euros in frozen assets held at Belgium’s Euroclear to provide Ukraine with a loan of up to 165 billion euros (about 193 billion dollars), repayable only if Russia pays war reparations. In effect, the loan is interest-free and amounts to a form of indirect confiscation of Russian assets.

Frozen assets are only one part of Europe’s leverage toolkit. Over the past three years, the European Union has imposed more than 19 broad sanctions packages on Russia, including restrictions on the energy sector, blocking access to financial markets, bans on the export of sensitive technologies, and measures targeting individuals and entities linked to the Kremlin.

One of the latest steps has been sanctions on Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet,” vessels used to circumvent oil sanctions and transport Russian crude to global markets. Europe has also proposed that Ukraine join the EU by 2027—that could structurally guarantee Kyiv’s long-term security but would also entail heavy economic and political commitments for Europe.

Internal European divisions have further complicated the equation. Hungary and Slovakia have openly opposed the use of frozen assets. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Putin’s closest European ally, described the decision as a “systematic violation of European law by the European Commission,” arguing that it was taken to “prolong a war that is clearly unwinnable.”

Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico, in a letter to European Council President António Costa, said he would refrain from any action that “involves covering Ukraine’s military costs for the coming years,” warning that “using frozen Russian assets could directly jeopardize US peace efforts.” Even Italy and Belgium, which sit in the middle of Europe’s political spectrum, have expressed concern about the legal and economic consequences of the plan.

Dual-track diplomacy: between support for Ukraine and fear of a “dirty deal”

Europe’s stance on peace in Ukraine is a complex mix of principled support and operational concerns. On the one hand, the EU reiterates its commitment to Ukraine’s survival, declaring that “Ukraine’s security must be guaranteed in the long term as the EU’s first line of defense.” Ursula von der Leyen has stated explicitly that the “need to strengthen Ukraine militarily and diplomatically” is at the core of discussions with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte.

According to reports, around 30 countries, including NATO members as well as Japan and Australia, are working on a “security guarantees framework” for Ukraine that would include assurances similar to NATO’s Article 5, which emphasizes collective defense. However, the nature of these guarantees remains unclear, and Rutte has explicitly said that “what we are discussing is not NATO membership, but rather forms of Article 5–type security guarantees for Ukraine.”

At the same time, Europe is deeply concerned that Trump’s peace plan could lead to a “fragile peace” that fails to ensure European security. European analysts warn that if an agreement is imposed on Ukraine involving large-scale territorial concessions, severe restrictions on Kyiv’s military, and the absence of credible security guarantees, it would effectively encourage Russia to pursue future aggression—whether against Ukraine or other neighbors.

Another major European concern is Russia’s economic and military recovery following the lifting of sanctions. Trump’s peace plan предусматривает a gradual removal of some sanctions. This comes as Russia’s economy, in recent years, has managed to offset a significant portion of the impact of sanctions with the help of China, India, and other new trading partners. Europeans fear that a rapid rollback of sanctions would give Russia the opportunity to rebuild its military capabilities and, in the not-too-distant future, once again become a serious threat to European security. For this reason, the EU insists that part of the sanctions be retained as “leverage,” allowing them to be reimposed if Moscow violates any agreement.

The impact of Trump’s return to the White House on this equation is undeniable. With his “America First” approach and a desire to reduce military and financial commitments in Europe, Trump clearly holds a different view on continued support for Ukraine. In recent interviews, he has criticized Zelensky in an angry tone, saying that “American public opinion can no longer tolerate the costs of this war.”

Trump also said at a White House press conference that he had spoken to European leaders about Ukraine “in very harsh terms,” adding: “We don’t want to waste our time. They want us to go to Europe for a meeting over the weekend, but it depends on what they come back with.”

This threatening tone suggests that Trump is no longer willing to play the role of coordinator among European allies and is seeking a rapid deal that would carry fewer political and economic costs for Washington.

According to experts, Europe’s reactive strategy suffers from serious structural weaknesses. The old continent still lacks an independent army, integrated defense infrastructure, and the political consensus needed to bear heavy defense costs. Studies show that much of Europe’s weapons systems depend on non-European components and technologies, and that Europe’s military supply chain is severely slow and inadequate for mass-producing the weapons Ukraine needs. In other words, Europe wants to play a role in shaping peace, but it still lacks the tools required to impose its will.