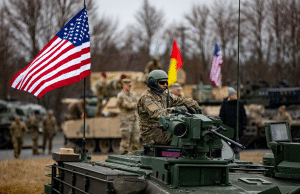

PNN – Washington’s two-year deadline for Europe to shoulder NATO’s defense burden exposes deep structural, technological, and budgetary challenges that make its fulfillment appear unrealistic—at least in the foreseeable future.

For decades, America’s security umbrella has served as the main pillar of Europe’s defense; however, Washington—now in Trump’s second administration—seeks to change this equation. On December 5, 2025 (15 Azar 1404), a sensitive meeting was held in Washington which, according to observers, may mark a turning point in Europe’s security history.

In this meeting, Pentagon officials informed European diplomats that Europe must, within the next two years—by 2027—assume a major share of NATO’s conventional defense capabilities, from military intelligence gathering to missile systems. This message, however, was accompanied by a warning: if Europe fails to meet this deadline, the United States may reduce its participation in some of NATO’s defense coordination mechanisms. Such a deadline, which alters the way Washington cooperates with its most important military partners, has raised serious questions about the practicality of Europe’s military autonomy.

The idea of Europe’s military independence and self-sufficiency from the United States is not new. For years, European leaders—especially French President Emmanuel Macron—have emphasized the need for “European strategic autonomy.” In his historic Sorbonne speech in September 2017, Macron introduced the concept of European sovereignty and an independent operational capability for Europe, calling for the creation of a joint European army. He has consistently stressed that Europe cannot rely on the United States for its security forever. Despite these efforts, eight years later the fundamental question remains unanswered: can Europe truly defend itself without America’s security umbrella?

Washington’s deadline: political pressure or a real threat?

The Pentagon’s message to European delegations in Washington was unprecedented. According to a Reuters report citing five informed sources, U.S. Defense Department officials stated during the meeting that they are not satisfied with Europe’s progress in strengthening its defense capabilities since Russia’s large-scale attack on Ukraine in 2022.

This comes despite the fact that Europe’s defense expenditures have risen significantly over the past three years. According to figures from the European Defence Agency, the defense budget of European Union member states increased from 218 billion euros in 2021 to 326 billion euros in 2024—an increase of more than 49 percent. For 2025, it is projected that this number will reach 392 billion euros, equivalent to 2.1 percent of GDP.

Nevertheless, Washington does not consider these increases sufficient. At the NATO summit held in The Hague in June 2025, member states committed to raising their defense spending to 5 percent of GDP by 2035—3.5 percent allocated to core defense expenditures and 1.5 percent to defense infrastructure, cyber-security, and related areas. This ambitious goal shows that even Europeans themselves recognize they need time until 2030; yet now the Pentagon has presented a 2027 deadline.

The issue is that it remains unclear whether this deadline reflects the official position of the Trump administration or merely the view of certain Pentagon officials. During the 2024 election campaign, Trump repeatedly criticized European allies and even said he would encourage Vladimir Putin to attack NATO countries that do not pay their fair share. However, at the NATO summit in June, Trump praised European leaders for agreeing to raise their annual defense spending target to 5 percent of GDP. These contradictions indicate that Washington’s policy toward Europe remains unsettled.

Capability gaps: from air defense to military intelligence

A realistic review of Europe’s military self-sufficiency challenge reveals that the continent lacks essential capabilities in critical areas where it has relied on the United States for decades. One of the most important gaps concerns America’s capabilities in the fields of military intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR).

According to European experts, space- and satellite-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities are the area in which Europe’s gap with the United States is widest. Based on data from the Union of Concerned Scientists in May 2023, the United States possessed 246 military satellites, while all European NATO members combined had only 49, with France leading at 15 satellites.

This stark disparity shows that Europe will not, for years to come, be able to establish an independent alternative to America’s space-based surveillance capabilities. Raphael Loss of the European Council on Foreign Relations warns: “Without a significant improvement in space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities, other efforts to develop European capabilities—including long-range strike approaches with very long kill chains—will face major obstacles.”

Air and missile defense is another critical area. The experience of Ukraine highlighted the vital importance of integrated air defense combined with deep-strike capabilities, yet Europe lacks advanced electronic warfare systems capable of suppressing enemy air defenses. In 2025, the European Union launched the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) with a budget of over 500 million euros to urgently supply ammunition to Ukraine and help member states replenish their stocks, but these efforts will take years to yield results.

In the domain of command and control, Europe’s infrastructure remains heavily dependent on U.S. personnel and systems. Moreover, Europe lacks sufficient access to aerial refueling capacity and strategic airlift, and NATO’s rapid-deployment capability continues to rely on the United States. According to the EU Defence Commissioner’s estimate in March 2025, an additional 70 billion euros in investment is still needed to adapt Europe’s air, rail, road, and maritime infrastructure for the rapid movement of forces and equipment.

European forces have for decades been designed to operate within U.S.-led coalitions, not independently and on a large scale. Even with improved intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities, operational coordination among European militaries would remain difficult; it is the United States that today ensures interoperability among NATO forces through the integration of personnel, systems, and command structures.

Structural obstacles: why the two-year deadline is unrealistic

Even if Europeans were to seriously pursue military self-sufficiency, numerous structural obstacles make meeting the 2027 deadline almost impossible.

The first challenge is production delays in military equipment orders. While U.S. officials have encouraged Europe to purchase more American-made systems, the delivery of some of the most valuable U.S. weapons and defense systems takes years. For example, if European countries were to order Patriot air-defense systems or F-35 fighter jets today, their delivery could extend well into the 2030s.

The second obstacle is the limited capacity of Europe’s defense industry. According to a report by the consulting firm Oliver Wyman in August 2025, Europe’s defense sector will require more than 250,000 additional skilled engineers and technicians over the next five years to meet the current and growing market demand—an amount equal to more than 25 percent of the sector’s existing workforce. This labor shortage is only part of the problem; converting production capacity from adjacent industries into defense manufacturing—especially in electronics and precision mechanics—comes with serious complexities.

The third challenge is the fragmentation of Europe’s defense industry. Unlike the United States, which has consolidated its defense sector into a number of large integrated corporations, Europe has numerous national players that mostly operate within their domestic markets and produce at relatively low volumes. Major defense companies such as Leonardo, Dassault, Thales, and Rheinmetall are based in different countries, and joint European programs often derail due to differing military requirements, national manufacturers’ production-load constraints, or international political considerations—particularly those involving the United States.

A clear example of this problem is the joint French–German projects to develop a sixth-generation fighter jet (SCAF) and a next-generation battle tank (MGCS), commitments that President Macron persuaded then-Chancellor Angela Merkel to make in 2017. These programs now face serious difficulties and are at risk of failure. Meanwhile, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Japan are working on the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) to build another stealth fighter, and this duplication of efforts further disperses scarce resources.

The fourth obstacle is financial constraints. Even with rising defense budgets, many European countries operate within tight fiscal environments. Raising defense spending to 3.5 to 5 percent of GDP would require significant cuts to other areas of public expenditure. In Germany—the largest European economy—adding just 2 percent to defense spending would mean nearly an additional 100 billion euros per year. For a country whose number of retirees increased by about 50 percent between 1991 and 2022, making decisions to reduce social benefits will not be easy.

The fifth challenge is the lack of political coordination at the European level. While Eastern European countries such as Poland and the Baltic states—feeling a more direct threat from Russia—have rapidly increased their defense budgets (Poland became NATO’s largest defense spender relative to GDP in 2024 at 4.12 percent), Southern European countries like Italy and Spain have not followed the same trajectory. This divergence in threat perception and national priorities makes achieving a unified European approach exceedingly difficult.