MUNICH/BERLIN/FRANKFURT: Germany is turning to artificial intelligence, drones and even insect-inspired surveillance tools to modernise its military like never before.

What once seemed like science fiction — including robot cockroaches that gather real-time data on enemy positions — is now part of a growing defence industry that’s gaining serious momentum.

Driven by Russia’s war in Ukraine and rising global tensions, a German defence start-up is leading a bold shift in how the country sees national security — and its place in Europe’s future.

Gundbert Scherf is the co-founder of Germany’s Helsing, that has developed into Europe’s most valuable defence start-up.

Scherf had to work hard to attract investment after launching his company – which produces military strike drones and battlefield AI – four years ago.

Now, that’s the least of his concerns. The Munich-based company more than doubled its valuation to $12 billion at a fundraising last month.

“Europe this year, for the first time in decades, is spending more on defence technology acquisition than the US,” said Scherf.

The former partner at McKinsey & Company says Europe may be on the cusp of a transformation in defence innovation akin to the Manhattan Project – the scientific push that saw the US rapidly develop nuclear weapons during World War Two.

“Europe is now coming to terms with defence.”

Reuters spoke to two dozen executives, investors and policymakers to examine how Germany – Europe’s largest economy – aims to play a central role in rearming the continent.

Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s government views AI and start-up technology as key to its defence plans and is cutting bureaucracy to link start-ups directly to the upper ranks of its military, the sources told Reuters.

Shaped by the trauma of Nazi militarism and a strong post-war pacifist ethos, Germany long maintained a relatively small and cautious defence sector, sheltered by US security guarantees.

Germany’s business model, marked by a deep aversion to risk, also favoured incremental improvements over disruptive innovation.

No more. With US military support now more uncertain, Germany – one of the biggest backers of Ukraine – plans to nearly triple its regular defence budget to around 162 billion euros ($175 billion) per year by 2029.

Much of that money will go into reinventing the nature of warfare, the sources said.

Helsing is part of a wave of German defence start-ups developing cutting-edge technology, from tank-like AI robots and unmanned mini-submarines to battle-ready spy cockroaches.

“We want to help give Europe its spine back,” said Scherf.

Some of these smaller firms are now advising the government alongside established players – so-called primes such as Rheinmetall RHMG.DE and Hensoldt HAGG.DE – that have less incentive to focus on innovation, given their long backlogs for conventional systems, one source said.

A new draft procurement law, approved by Merz’s cabinet on Wednesday, aims to reduce hurdles for cash-strapped start-ups to join tenders by enabling advance payment to these firms.

The law would also allow authorities to limit tenders to bidders inside the European Union.

Marc Wietfeld, CEO and founder of autonomous robots maker ARX Robotics, said a recent meeting with German defence minister Boris Pistorius highlighted just how far thinking in Berlin had shifted.

“He told me: ‘Money is no longer an excuse – it’s there now’. That was a turning point,” he said.

Germany in the lead

Since Donald Trump’s return to the political stage and his renewed questioning of America’s commitment to NATO, Germany has pledged to meet the alliance’s new target of 3.5% of GDP on defence spending by 2029 – faster than most European allies.

Officials in Berlin have emphasised the need to build a European defence industry rather than rely on US companies. But scaling up industry champions in Germany – and Europe in general – remains challenging.

Unlike the United States, Europe’s market is fragmented. Each country has its own procurement standards for fulfilling contracts.

The United States, the world’s top military spender, already has an established stable of defence giants such as Lockheed Martin and RTX, and an edge in key areas including satellite technology, fighter jets and precision-guided munitions.

Washington also began supporting defence tech start-ups in 2015 – including Shield AI, drone maker Anduril, and software company Palantir – by awarding them portions of military contracts.

European start-ups until recently struggled with little government support.

But an analysis by Aviation Week in May showed Europe’s 19 top defence spenders – including Turkey and Ukraine – were projected to spend 180.1 billion this year on military procurement, compared to 175.6 billion for the United States. Washington’s overall military spending will remain higher.

Hans Christoph Atzpodien, head of Germany’s security and defence sector association BDSV, said one key challenge was that the military’s procurement system was tailored to established suppliers and not well suited to the pace at which new technologies emerge.

Germany’s defence ministry said in a statement it was taking steps to accelerate procurement and better integrate start-ups to make new technologies quickly available to the Bundeswehr.

Annette Lehnigk-Emden, head of the armed forces’ powerful procurement agency, highlighted drones and AI as key emerging areas for development.

“The changes they’re bringing to the battlefield are as revolutionary as the introduction of the machine gun, tank, or aeroplane,” she told Reuters.

Spy cockroaches

Sven Weizenegger, head of the Cyber Innovation Hub – the Bundeswehr’s innovation accelerator – said the war in Ukraine had also changed public attitudes, removing the stigma around working in the defence sector.

“Germany has developed a whole new openness towards the issue of security since the invasion,” he said.

Weizenegger said he now receives 20–30 LinkedIn requests a day, compared to maybe 2–3 per week back in 2020, with ideas for developing defence technologies.

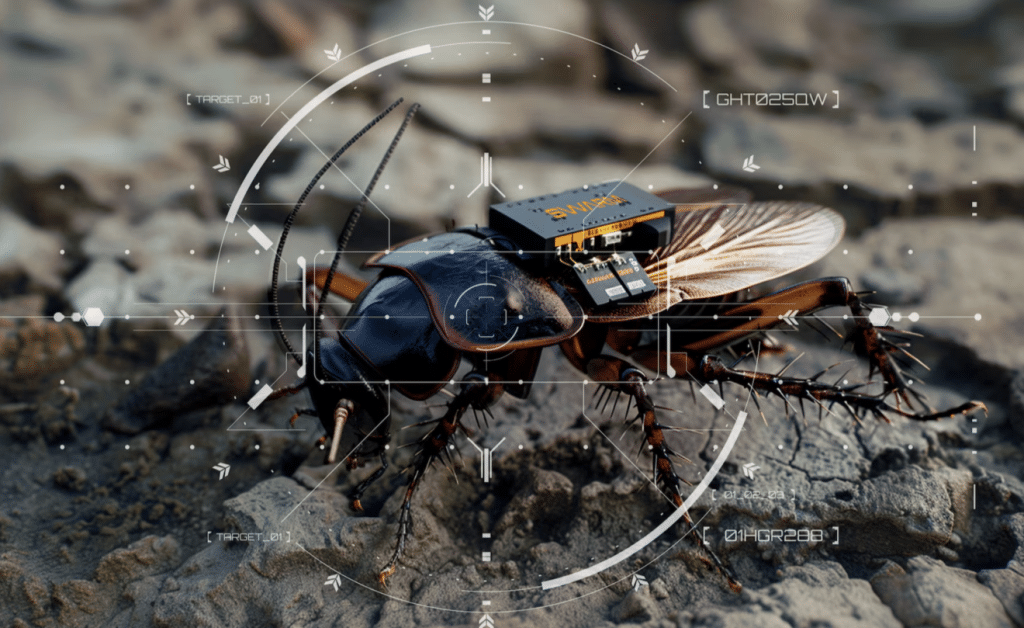

Some of those ideas verge on science fiction – such as Swarm Biotactics’ cyborg cockroaches, equipped with miniature backpacks enabling real-time data collection via cameras.

Electrical signals should allow humans to control the insects’ movements remotely. The aim is to gather surveillance intelligence in hostile environments – such as details on enemy positions.

“Our bio-robots – based on living insects – are fitted with neural stimulation, sensors, and secure communication modules,” said CEO Stefan Wilhelm. “They can be steered individually or act autonomously in swarms.”

In the first half of the 20th century, German scientists pioneered many military technologies that became global standards – from ballistic missiles to jet aircraft and guided weapons. But following its defeat in World War II, Germany was demilitarised and its scientific talent dispersed.

Wernher von Braun, who created the first ballistic missile for the Nazis, was one of hundreds of German scientists and engineers taken to the United States after the war, where he later worked at NASA and developed the rocket that took the Apollo spacecraft to the Moon.

In recent decades, defence innovation has been a powerful economic engine. Technologies like the internet, GPS, semiconductors and jet engines began in military research before transforming civilian life.

Hit by soaring energy prices, falling demand for exports and growing competition from China, Germany’s $4.75 trillion economy has contracted over the past two years. Expanding military R&D could offer an economic boost.

“We just need to get into this mindset: a strong defence industrial base means a strong economy and innovation on steroids,” said Markus Federle, managing partner at defence-focused investment firm Tholus Capital.

Escaping ‘the valley of death’

European investors’ risk aversion has previously held back start-ups, which struggled to survive the ‘valley of death’ – the crucial early phase when costs are high and sales low.

But increased defence spending across Europe following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sparked investor interest.

Europe now boasts three start-ups with unicorn valuations above $1 billion: Helsing, German drone maker Quantum Systems, and Portugal’s Tekever.

“There’s a lot of pressure now on Germany being the lead nation of European defence,” said Sven Kruck, Quantum’s chief strategy officer.

Germany has become Ukraine’s second-largest military backer after the United States. Approvals that once took years now take months, and European start-ups have had the chance to test their products on the ground, several sources said.

Venture capital funding for European defence tech reached $1 billion in 2024, up from just $373 million in 2022, and is expected to rise further this year.

“Society has recognised that we have to defend our democracies,” said Christian Saller, general partner at HV Capital, an investor in both ARX and Quantum Systems.

Venture capital has grown faster in Germany than elsewhere, according to data analysed by Dealroom for Reuters. German defence start-ups have secured $1.4 billion over the past five years – more than any other European country – followed by the UK.

Jack Wang, partner at venture capital firm Project A, said many German start-ups – leveraging the country’s engineering expertise – are adept at integrating existing components into scalable systems.

“Talent quality in Europe is incredibly high, but overall, there’s no country with better engineering talent than Germany,” he said.

Weakness in Germany’s automotive sector means there is manufacturing capacity to spare, especially in the Mittelstand – the small and medium-sized enterprises that form the backbone of Germany’s economy.

Stefan Thumann, CEO of Bavarian start-up Donaustahl, which makes loitering munitions, said he receives 3 to 5 applications daily from workers leaving automotive firms.

“The start-ups just need the brains to do the engineering and prototyping,” he said. “And the German Mittelstand will be their muscles.”